Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 19th installment.

I barely mentioned the back-matter in the opening three issues of Watchmen last week, but the excerpts of former Nite Owl Hollis Mason’s Under the Hood—his fictionalized memoir as written by Alan Moore—are essential pieces of the Watchmen text. In the three excerpts Moore provides the connective tissue for the world building that’s of such fundamental importance to the overall story of this alternate reality. Mason’s memoir gives more information about the early days of the superhero, from the down-to-Earth perspective of someone who actually lived through it.

And Mason’s distinctive point of view is important too, because even though Moore and Gibbons try, throughout the series, to wrestle with the conventions of comic book storytelling and provide a sense of seeing the world through various sets of eyes, comics, like cinema, are forced to present an objective depiction of reality. We see what’s in front of the camera, or inside the panels, and it’s difficult not to take it literally. We can speculate on what happens between the frames, but what’s shown is reality as far as we know.

With Under the Hood, Moore can adopt a much more subjective point of view. And we get the sense that Hollis Mason is being forthright and honest to his own experiences, but he’s also glossing over some more troubling aspects of the Minutemen’s past. It’s a celebrity autobiography, with some warts displayed, but others covered up a bit to protect some of his friends.

And yet, because Moore and Gibbons know that in the comic book story itself, we will take things as they are shown to us, they can use the visuals to mislead. In a detective story, it’s not always what you can and can’t see, but how you interpret the visual evidence. How you connect the dots.

Watchmen#4 (DC Comics, December 1986)

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons connect a lot of the dots for us in this issue, not in terms of the overall murder mystery that drives the main plotline, but in the way the history of this superhero world has been pieced together. This is the Dr. Manhattan spotlight issue, where we learn who he is and how he came to be and it ends with an essay by the fictional Professor Milton Glass who tells us, “our leaders have become intoxicated with a heady draught of Omnipotence-by-Association, without realizing just how his very existence has deformed the lives of every living creature on the face of this planet.”

That’s Dr. Manhattan he’s talking about, of course. The Captain Atom of the Watchmen universe. And its only Superman.

Reportedly, Alan Moore’s original plot for Watchmen only amounted to six issues of content, yet he had contracted to deliver twelve issues, and that’s where the quite-effective idea of alternating “story” issues with “character” issues came to be. In general, the odd-numbered issues advance the main story about the death of the Comedian and the investigation that leads to uncovering a much larger conspiracy. The even-numbered issues focus on the characters, and provide layered flashbacks into their pasts, presents, and, with issue #4, maybe even some futures.

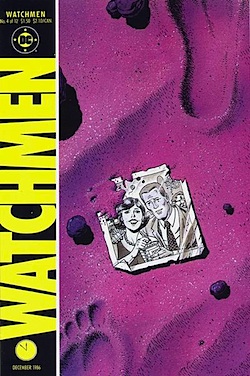

Watchmen#4 is notable, not just for telling the story of the most powerful being in its universe, but also because it’s the only issue of the series that features people on its cover. Think about that. Twelve issues of an American superhero comic book series and not one of them shows any kind of action pose. Not one of them even depicts any of the main characters in any recognizable form. Rorschach’s hat appears in a reflected puddle of water in a later issue. Some amorphous forms reflect off the glass of a viewscreen in another, but this is a series with covers that emphasize its status as a story about shapes and symbols. Humans fill the inside of the stories, but they never appear on the outside.

Except here, and it’s a tattered photograph on the surface of Mars. Jon Osterman and Janey Slater, a memento of a past long gone for most, but eternally present for the temporally aware Dr. Manhattan.

Out of all the early issues of Watchmen issue #4 is one of the least interesting to reread, though, mostly because its framed as a character piece, but the character is a dispassionate, disengaged near-omnipotent superbeing. Moore and Gibbons use the issue to present so much exposition about Dr. Manhattan and the essential fragments of his life before and after the accident that led to his superhumanity that the story works, as its own clockwork symbolism indicates, as a delicate piece of a much larger machine. But it’s not a very interesting piece on its own, not in comparison to the rest of the series.

This one’s too clever, too systematic in its delivery, with Dr. Manhattan’s narrative captions providing a dry retelling of his life’s events and the cumulative loneliness of being able to participate in all times at once, on a subatomic level. When he builds his crystalline clockwork palace on Mars, we can’t miss the symbolism—this is Jon Osterman, the son of a watchmaker, connecting with his past in the most artificial way possible—but the symbolism alone isn’t enough to make it compelling. The first time through, yes. But not upon rereading.

Still, like any spring or wheel in a pocket watch, the whole thing can’t work without it.

Watchmen #5 (DC Comics, January 1987)

“Fearful Symmetry” is the title, and it’s the structure of the issue as well.

In Watching the Watchmen, the 2008 behind-the-scenes book which relies almost totally on Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen process art, Gibbons reveals that the script for this issue came a few pages at a time. He was drawing it without seeing the entire script.

Plenty of comics likely end up drawn that way—though it’s obviously not the preferred method for anyone—but what makes that approach remarkable here is that Watchmen #5 is visually symmetrical. The panel layouts and pacing read the same forward or backwards, with a climactic action scene occurring right in the middle of the issue, the center gutter bisecting a giant panel of Ozymandias battering his attacker.

As I mentioned last week, for a superhero comic, this series is astonishingly short on action scenes, on superhero fisticuffs, but the centerpiece of this issue not only breaks free from the gridded structure of the rest of the series, but, with its seven large panels spread across two pages, it shows a hero in full fighting mode, deflecting bullets, bashing a bad guy, diving toward victory.

It’s framed as if to say, “here’s what you’ve been waiting for, comic book fans! All-out action, thanks to the golden-haired Ozymandias!”

That should be a glaring hint that something’s wrong with the scene.

It’s a superhero action scene in a comic, in a series, that has subverted or ignored superhero action almost completely. But here, it becomes the focus, in exaggerated form.

It’s a clue to the reader, though we don’t find out what it means until later in the series. But this Ozymandias fight sequence, where he defends himself against a would-be assassin, is completely staged. Ozymandias, as the ultimate villain of Watchmen (if we can call him that), has hired someone to kill him, just so he could look like another potential victim of whoever killed Edward Blake. As we later learn, Ozymandias himself killed Blake, to protect his own nefarious-and-insane-if-well-intentioned plot.

That’s why the scene in this middle of this issue reads like typical superhero action. It’s completely phony. Yet, upon an initial reading, it would just seem surprisingly exciting.

Watchmen is good.

This is also the issue where things fall apart for Rorschach. He’s set up, the captured by the police, but his futile attempts to fight back and escape are confined to a nine-panel grid. He’s restrained, constricted, and can only lash out and his captors. As he jumps from a third story window (again, not in a splash page or even a large panel, just in 1/9th of the page) he’s no superhuman action star. Just a small man, tumbling to the ground awkwardly, kicked in the face by jackboots.

He doesn’t get a glorified action-packed scene where he looks like a hero. No, reality has crashed in upon him. Upon the genre.

The back-matter for this issue gives us the only non-Gibbons art in the entirety of Watchmen as we get an article about the real-life Joe Orlando and the fake history of pirate comics in this alternate reality. The essay mentions the disappearance of pirate comic writer Max Shea—an embedded clue relating to the global conspiracy—but it’s a winking piece by Moore (of the type he actually used to write for the U.K. fanzines) in which he gets to develop the history of comic book culture in the Watchmen world.

By itself, it almost justifies the repeated, in story, refrain of “Tales of the Black Freighter” the pirate comic juxtaposed with the main Watchmen events throughout the series. But as a reader, I still find the Black Freighter stuff ineffective. I get the thematic parallels, and the “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” kind of subtext it provides to the story. And I appreciate the absurd visuals, with the lone survivor atop a raft made of killer shark. But it’s difficult not to see the “Tales of the Black Freighter” excerpts as a diversion from the text of Watchmen even though it’s deeply embedded within it, written and drawn by Moore and Gibbons. Still, a diversion it remains, and if it’s one I understand from a thematic, structural perspective, it’s not one I particularly enjoy.

Watchmenis good, but it’s not always great.

Ah, what am I saying? It’s pretty great.

Watchmen #6 (DC Comics, February 1987)

And then there’s this: the story of Rorschach.

This story has its own kind of symmetry, with the ink blot in the opening scene recurring in the end, as Dr. Malcolm Long contemplates the abyss he’s stared too deeply into.

One of the conceits of this issue—a comic which never cuts away from Rorschach’s story—is that the deranged Walter Kovacs has confronted a reality so bleak that the only rational response was to become irrational, to become as uncompromisingly harsh as the world around him, and that unrelenting attitude ultimately infects his psychoanalyst. Dr. Long begins speaking in a halting, blunt manner, pulls himself away from humanity, and becomes, if not corrupted, then deeply changed by his interactions with his patient.

The conversion of Dr. Long is a bit of a failure, narratively, and it seems like a too-easy resolution for the issue. There’s really no need for it, since the impact of the loss of innocence revelations (and Walter Kovacs began his life far from grace) is more powerful on the reader. It’s the reader who needs to undergo a bit of a conversion, or at least self-reflection, as he or she finds out how Rorschach became Rorschach and all that it implies.

Until this issue, Rorschach was the unrefined costumed detective. He may have “narrated” large chunks of the story (via his journal entries) in extreme, purple prose, but so far, he’s the one who has been right about most things. He’s the madman who can see the truth that others ignore. The Shakespearean fool, but with only the blackest sense of humor and no self-awareness at all.

In this issue, we find out how he ended up that way, and in his interviews with the Doctor he reveals that he used to play the role of Rorschach, but it took a particular incident to turn him into Rorschach. His face is now the black viscous fluid in the synthetic white fabric of his mask. His identity as a human has been superseded by this vigilante persona he’s created.

This notion of the superhero identity—the mask—supplanting the humanity of the wearer has become a cliché since the time of Watchmen. Alan Moore probably wasn’t the first to address identity theory in the context of superhero comics, but through Watchmen he brought that kind of thinking to a mass audience, and it influenced every costumed superhero story that followed, whether the writers and artists directly addressed its influence or not.

But with Rorschach, Moore and Gibbons provide an unusual origin story. Unlike the typical vigilante hero, his parents were not murdered by criminals, nor was he a thrillseeker looking for adventure. Neither was he a late-night law enforcer or a protector of the streets.

He may have started out with some of those elements, but Walter Kovacs led a troubled life since childhood. He was raised by an abusive prostitute and violently bullied by his peers. He adopted the Rorschach identity, but not the persona, seemingly to give some kind of meaning to his life. To join some kind of righteous cause. He patrolled with Nite Owl. He helped keep the criminal underworld at bay. But a 1975 kidnapping case showed him how horrific the world really was, and the direct, unyielding, abrupt-speaking Rorschach was born.

Moore and Gibbons present a superhero who is only a superhero, only ever was a superhero, because he was psychologically damaged. And becomes most effective after he has gone insane.

Like Watchmen as a whole, the characterization of Rorschach turns the lens back into the genre itself, and reveals the pathology that has been underlying costumed superheroics all along.

What’s sad is that the writers inspired by Moore applied his approach to the likes of Batman (I think Moore’s Rorschach had more of an influence on late 1980s/early 1990s Batman comics than even Frank Miller’s landmark work with the character) and Green Arrow and Dr. Fate and dozens of other characters originally created for children.

The loss of innocence embodied in this issue affected far more than the characters in this one story.

Yet, with Rorschach, what are we left with? He’s still the most popular character from the series—his “I’m not locked up in here with you. You’re locked up in here with me” line to his fellow prisoners is practically a catchphrase in some circles. He’s deranged, grotesquely violent, and yet sympathetic because of his past and because he restricts his brutal rage to those who “deserve” it. He’s also the only character in the story who seems to be able to figure out what’s really going on. He’s positioned as the hero of the series for a huge chunk of it.

He’s a reactionary, ultra-violent vigilante, created by the ultra-liberal Alan Moore, perhaps as a commentary on the American superhero, but not in a mocking, dismissive way.

Rorschach, a completely appalling character by almost any standard, is the beating heart of Watchmen. And we’re locked up inside the nine-panel grid with him. Hurm.

NEXT: Watchmen Part 3, Where Plot Takes Over

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.